Urban Heterogeneity and Technological Innovation in the Roman Empire (2023)

How are we to understand technological innovation in the Roman Empire? In which way did the Roman Empire transform or even enhance (ongoing) processes of technological innovation in the ancient Mediterranean? This article explores the relation between imperial hegemony, social heterogeneity, and technological change. The abundance of archaeological and epigraphic evidence makes it possible to both reconstruct a historical geography of urban heterogeneity on the global scale, and to explore its impact at the level of individual regions and cities. This article argues that urban heterogeneity became unequally distributed over the Roman Empire, peaking in the core of the empire in central Italy. Emerging heterogeneity created ideal circumstances for technological innovation, and several key innovations from the Roman period can not only be associated with these extremely heterogeneous micro-regions, but also seem to be facilitated by their very heterogeneity. This perspective adds a new dimension to debates about technological innovation in the Roman Empire that moves beyond the opposition between optimists and pessimists that has long dominated scholarship.

Bibliographical details

Type

Article in peer-reviewed journal, 2023. Publication of a June 2022 conference on Urban Heterogeneity in Copenhagen, where I gave an invited talk.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2023). ‘Urban Heterogeneity and Technological Innovation in the Roman Empire’. Journal of Urban Archaeology 8: 127–145.

Open Access

The chapter was published in open access (doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1484/J.JUA.5.135662).

"En wij dan?" Het dekolonisatieonderzoek en de postkoloniale ontheemden (2023)

Ruim twee maanden na de presentatie van het samenvattende rapport van het NIOD-onderzoek naar de dekolonisatieoorlog in Indonesië organiseerde de Tweede Kamer op 30 mei 2022 een rondetafelgesprek waarin aan organisaties van belangengroepen gevraagd werd te reageren op het rapport en daarover met Kamerleden in gesprek te gaan. De vertegenwoordigers van Indische en Molukse organisaties waren die dag eensgezind in hun boodschap: deze postkoloniale migrantengroepen, wier families zonder uitzondering hard geraakt waren door het dekolonisatieproces, voelden zich in het rapport nogal over het hoofd gezien. Namens de stichting Pelita, die opkomt voor de belangen van Nederlanders met een (familie)verleden in Indië, verwoordde Rocky Tuhuteru het als volgt: ‘er is een groot gevoel van miskenning, niet alleen in de Molukse gemeenschap maar zeker ook, als ik dat zo namens hen mag zeggen, in de Nederlands-Indische gemeenschap en in de totokgemeenschap’.

Wat gebeurde hier? Waarom waren vertegenwoordigers van een aantal groepen die in het dekolonisatieproces een centrale rol hadden gespeeld collectief zo ontevreden over dit enorme onderzoek, waar kosten noch moeite gespaard waren om de dekolonisatieoorlog van zoveel mogelijk zijden te belichten? In dit artikel wil ik proberen deze tegengeluiden inzichtelijk te maken, en betoog ik dat meer gedaan had kunnen worden om te anticiperen op de noden van deze groepen postkoloniale ontheemden, die door deze periode in sterke mate persoonlijk gevormd zijn. In dat kader is het allereerst belangrijk goed te begrijpen hoe de dekolonisatieoorlog en de jaren hierna eruitzagen vanuit het perspectief van de mensen die in Nederlands-Indië waren geboren, getogen en geworteld, maar uiteindelijk geen deel zouden worden van Indonesië. De jaren die volgden op de Indonesische onafhankelijkheidsverklaring van 17 augustus 1945 waren voor al deze mensen onoverzichtelijk, chaotisch, en soms erg angstig, en voor velen stond de uiteindelijke uitkomst – een definitief vertrek uit de Indonesische archipel – volstrekt niet op voorhand vast. Dit maakt dat deze jaren voor de nakomelingen van deze mensen van existentiële betekenis zijn: antwoorden op vragen over waarom zij bestaan, waarom zij Nederlander zijn, en hoe zij zichzelf verhouden tot het Nederlandse koloniale verleden, hangen deels af van hun interpretatie van de gebeurtenissen in deze periode. Lees verder.

Bibliographical details

Type

Article in journal, 2023. Written at the request of the editors. Part of 'discussiedossier 'dekolonisatie'.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2023). ‘"En wij dan?" Het dekolonisatieonderzoek en de postkoloniale ontheemden’. Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 136.3: 263–270.

Open Access

The article was published in open access (DOI: 10.5117/TvG2023.3.007.FLOH).

Prosperity and Inequality: Imperial Hegemony and Neighbourhood Formation in the Cities of Roman Italy (2023)

What did emerging imperial hegemony do to urban communities in Roman Italy, and how does it shape the Roman cities we know so well? Urban landscapes in Late Republican Roman Italy came to accommodate increasing levels of socioeconomic inequality, and this profoundly changed the ways in which urban communities functioned. This chapter explores what that meant for processes of neighbourhood formation. Starting from the idea that inequality can be physically expressed through urban housing stocks, the paper analyses the impact of the increasing wealth inequality brought about by Roman hegemonic prosperity at the micro-level. It starts by identifying the mechanisms of urban development through which inequality could accumulate in urban space, and then proceeds to analyse the actual developments in Roman Italy, contrasting the nature of neighbourhood formation in mid-Republican Italy with that in Late Republican Italy.

The chapter argues that, in the decades that followed the Roman conquest of large parts of the Mediterranean, cities at the heart of Rome’s imperial network increasingly developed urban landscapes defined by inequality, and that this had immediate consequences for the ways in which these quarters could function in everyday practice, entrenching socioeconomic distinction and hierarchy permanently in the urban landscape. However, it is also clear that this did not work out in the same way in every city: in some places, such as Pompeii, inequality became much more strongly pronounced in an earlier period than in other cities (e.g. Norba, Ostia, Paestum, Herculaneum).

Bibliographical details

Type

Chapter in edited volume, 2023. Publication of a November 2021 conference on Neighbourhoods in Kiel, where I gave an invited talk.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2023). ‘Prosperity and inequality: imperial hegemony and neighbourhood formation in the cities of Roman Italy’, in A. Haug, A. Hielscher and A.-L. Krüger (eds), Neighbourhoods and City Quarters in Antiquity. Design and Experience. Berlin: De Gruyter, 157–173.

Open Access

The chapter was published in open access through De Gruyter (doi: 10.1515/9783111248097-010).

An institutional revolution? The early tabernae of Roman Italy (2022)

How can we understand economic innovation in antiquity, and what does it mean for our understanding of ancient economic history? This paper studies the appearance of a very common urban feature in the cities of Roman Italy - the taberna. The paper develops around three arguments. At a very general level, it argues that commercial facilities as architectural concepts should be seen as historical phenomena, meaning that their emergence in some form or another represents a development in the history of markets, and that architectural change constitutes a logical focal point for discussions about the history of markets. Second, more specifically, this paper will argue that this is particularly true for the Roman taberna, which becomes visible in our archaeological and textual record only at a relatively late point in Roman urban history, suggesting there may have been a preceding period in which this phenomenon did not play a role in everyday economic practice; indeed, it will be suggested that this period ended more recently than has commonly been assumed. Thirdly, this paper will argue that the taberna did not have any direct predecessors in the Greek world, as has sometimes been suggested, but was an innovation of Middle Republican Central Italy that at some point was picked up and further spread by both the Roman authorities and private investors. This innovation, it is argued, was so fundamental for the history of retail in Roman Italy that it should count as an ‘institutional revolution’: it profoundly transformed the rules of the game in everyday economic practice.

Together, these arguments serve to make the point that, when discussing the economies of the market in the Greco-Roman World, ‘innovation’ should be a leading historical concept. That is to say, the subliminal message of this chapter is that debates about Greco-Roman economic history should not so much be primarily interested in how markets worked, and how this fits – or does not fit – with our conceptualizations about pre-modern or modern economies; rather, they should aim to explore how market institutions and market practices developed over time and adapted to changing economic realities. This position should be taken as opposing itself to approaches to the Roman economy that unduly privilege structural analysis over historical development, often in terms strongly opposing the Roman past to the modern world. As this paper will highlight, this obliterates many changes and developments within the Roman world.

Bibliographical details

Type

Chapter in edited volume, 2022. Publication of a February 2019 conference organized in Kassel, where I gave an invited talk.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2022). ‘An institutional revolution? The early tabernae of Roman Italy’, in K. Ruffing and K. Droß-Krüpe (eds), Markt, Märkte und Marktgebäude in der antiken Welt. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz, 425–439.

Open Access

A PDF of this publication is available in Open Access via Leiden University (https://hdl.handle.net/1887/3561535).

Between Aesthetics and Investment. Close-Reading the Tuff Façades of Pompeii (2022)

Why did Pompeians suddenly - in the mid second century BCE - start building houses with façades of finely polished tufa ashlar? This chapter was published in a volume on architecture and the ancient economy edited by Monika Trümper and Dominik Maschek. It offers a qualitative assessment of the economic rationale underlying the transformation of building practice in mid-second century BCE Pompeii. In this period, local traditional building practice based on carefully stacked blocks of travertine was replaced by a much more varied building practice that combined mortar with a number of regional building materials, including tuff ashlar.

The chapter observes that the new practice partially started from aesthetic considerations, but emerged with a clear economic rationale that both minimized costs and anticipated upon return on investment. Putting these developments in a broader Italic context suggests that the emerging building practice was facilitated by the unique local material circumstances at Pompeii: the developments in building technology were to a large extent local in nature, and should be seen as independent of architectural change. This, in turn, suggests that understanding the building practices and construction economies of the Roman world depends to a significant level on qualitative, but contextualized analyses of developments at the local level.

Bibliographical details

Type

Chapter in edited volume, 2022. Publication of a 2019 conference organized at the Freie Universität Berlin, where I gave an invited talk.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2022). ‘Between aesthetics and investment. Close-reading the tuff façades of Pompeii’, in M. Trümper and D. Maschek (eds), Architecture and the Ancient Economy. Analysis archaeologica, monograph series 5. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 155–172. ISBN: 9788854912922.

Open Access

This publication is not currently (2023) available in open access. You can buy the volume here. For availability in libraries see worldcat.

Information Landscapes and Economic Practice in the Roman World (2021)

How did the Roman Empire transform the way in which people involved in longer-distance trade could get their information about local markets? How did economic information circulate within and between cities? What did the 'information landscapes' look like with which traders would have to familiarize themselves? This chapter was published in a 2021 volume on Managing Information in the Roman Economy, edited by Cristina Rosillo-López and Marta García Morcillo. It explores the reality of asymmetric information in Roman economic practice by analyzing the historical development of 'information landscapes' in the Roman world, and by assessing what these imply for the contexts in which asymmetric information could play a role in everyday transactions.

I started from the idea that space remains an underexplored issue in approaches to economic practice in the ancient world, even though it is clear that, particularly in the Hellenistic period and the early Roman Empire, the nature and the dynamics of space change drastically, within regions, they change as a consequence of political unification, economic integration, and urbanization and, within cities, they change because of developments in architectural practice and increasing monumentalization. The chapter discusses the nature and impact of these developments both at the regional level and the urban level.

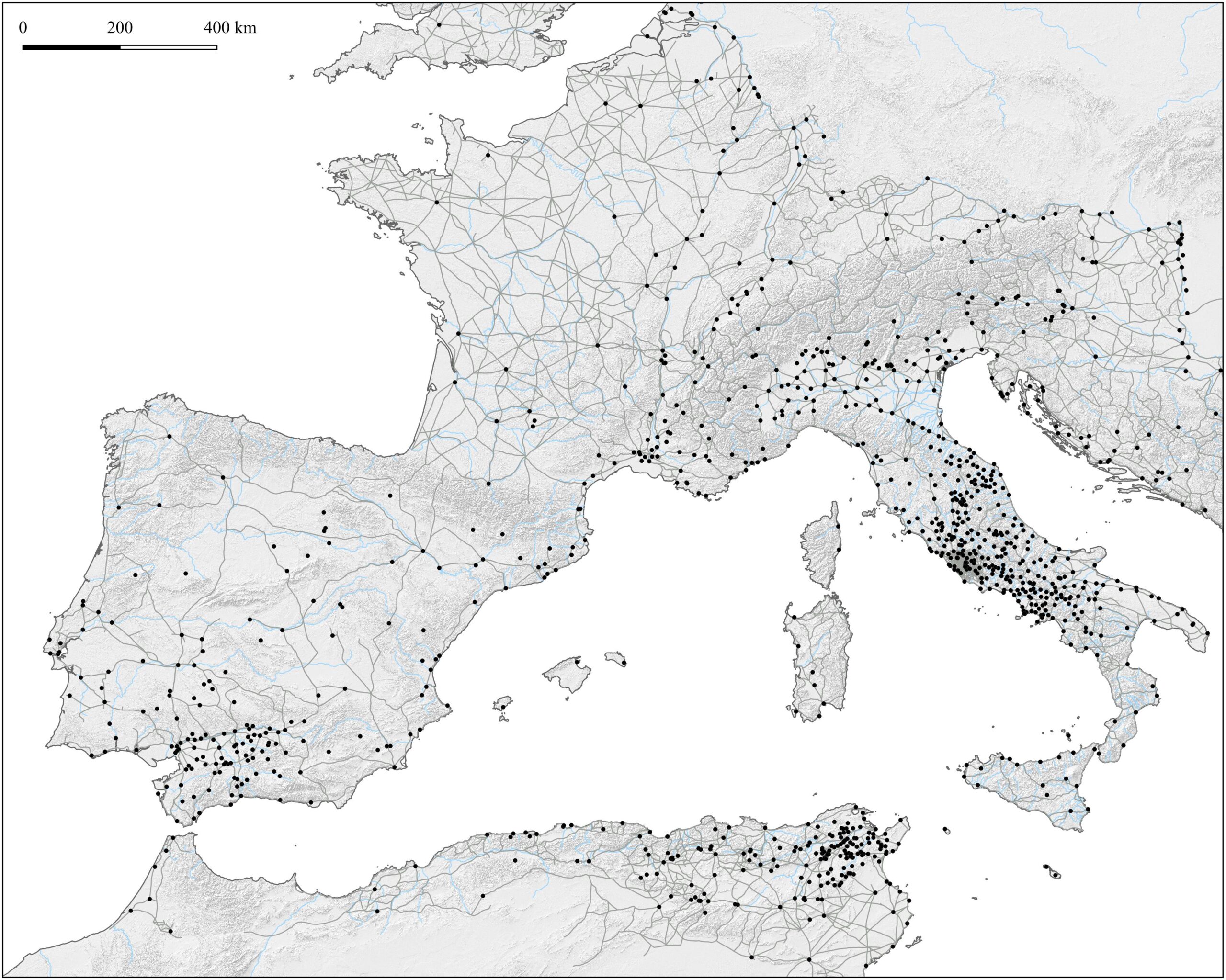

On the regional level, it observes the emergence, within the Roman Empire, of a limited number of clusters with a rather dense pattern of urbanization, implying strongly integrated regional information networks, and large areas were cities were fewer and further in between, suggesting more dispersed information networks, and a less natural circulation of information. These differences matter for economic actors operating at a supra-local level, and they have implications for the information strategies they can and cannot develop.

Within cities, there is an increasing development toward the construction of permanently accessible public facilities in and around the urban center which suggests a more predictable communication landscape, and therefore a more stable circulation of information, while the increasing amounts of shops along urban thoroughfares particularly in Roman Italy increased the density of urban information landscapes. This means that more, and better information was available to more people. The final section of the chapter explores what this means for information asymmetries, contending that this transformed the role that information assymetries played in everyday economic praxis.

Bibliographical details

Type

Chapter in edited volume, 2021. Peer reviewed. Publication of a 2018 conference organized in Sevilla, where I gave an invited talk.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2021). ‘Information landscapes and economic practice in the Roman World’, in C. Rosillo López and M. Garcia Morcillo (eds), Managing Information in the Roman Economy. Palgrave Studies in Ancient Economies. London: Palgrave, 205–228. ISBN: 9783030540999

Open Access

A PDF of this publication is available in Open Access via Leiden University (https://hdl.handle.net/1887/3216895).

Pictures

Featured Image

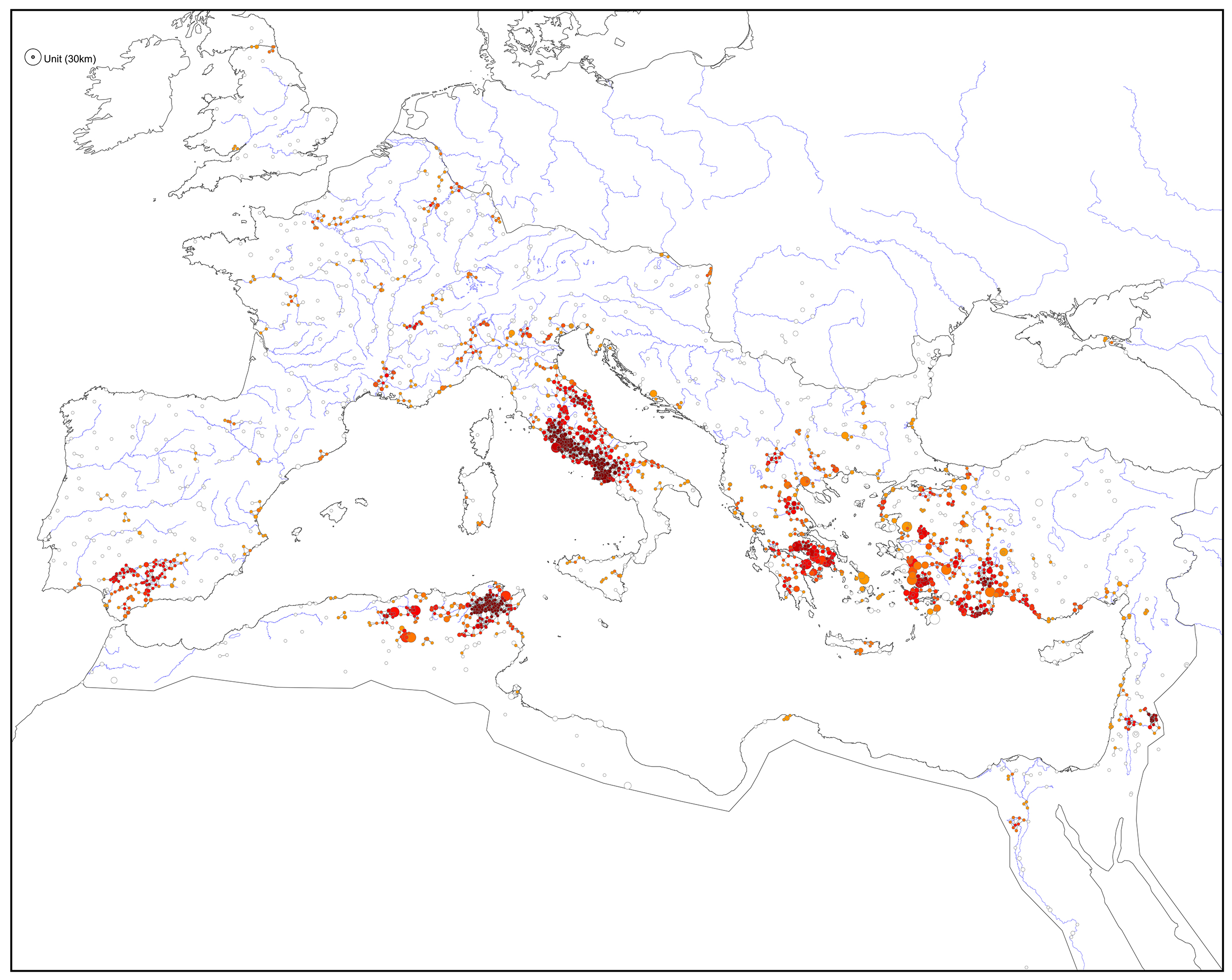

This map of the Roman world shows the spread of evidence for urban culture in the Roman world. It combines epigraphic evidence - inscriptions referring to key urban processes - with architectural remains of public buildings such as baths, theatres and amphitheatres, and it is color-coded to highlight the regional density of this evidence.

Artisans and Markets: the Economics of Roman Domestic Decoration (2019)

This article investigates how consumer demand shaped markets for high-quality domestic decoration in the Roman world and highlights how this affected the economic strategies of people involved in the production and trade of high-quality wall decoration, mosaics, and sculpture. The argument analyzes the consumption of high-quality domestic decoration at Pompeii and models the structure of demand for decorative skills in the Roman world at large. The Pompeian case study focuses on three categories of high-quality decoration: Late Hellenistic opus vermiculatum mosaics, first-century C.E. fourth-style panel pictures, and domestic sculpture.

Analyzing the spread of these mosaics, paintings, and statues over a database of Pompeian houses makes it possible to reconstruct a demand profile for each category of decoration and to discuss the nature of its supply economy. It is argued that the market for high-quality decoration at Pompeii provided few incentives for professionals to acquire specialist skills and that this has broader implications: as market conditions in Pompeii and the Bay of Naples region were significantly above average, the strategic possibilities for painters, mosaicists, and sculptors in many parts of the Roman world were even more restricted and, consequently, their motivation to invest in skills and repertoire remained limited.

Bibliographical details

Flohr, M. (2019), 'Artisans and Markets: The Economics of Roman Domestic Decoration', American Journal of Archaeology 123.1, 101-125. DOI: 10.3764/aja.123.1.0101.

This publication is available in open access through Leiden University (https://hdl.handle.net/1887/69905).

Innovation and Society in the Roman World (2016)

How did technological innovation affect Roman society? This article assesses the societal impact of Roman technological innovation. It starts from a critical engagement with past debate about technological progress, which over the past decades has been too strongly focused on economic growth, and a re-appreciation of the literary evidence for innovation, which points to a culture in which technological knowledge and invention were thought to matter. Then, it highlights two areas where the uptake of technology had a direct impact on everyday life: material culture, where the emergence of glass-blowing, a proliferation of metal-working, and innovation in pottery-production changed the nature and amount of artefacts by which people surrounded themselves, and construction, where building techniques using opus caementicium, arches and standardized building materials revolutionized urban and rural landscapes. A concluding discussion highlights the role of integration of the Mediterranean under Roman rule in making innovation possible, and the role of consumer demand in bringing it about.

Bibliographical details

Type

Article for online handbook. Peer reviewed. Written on invitation.

Reference

Flohr, M. (2016), 'Innovation and Society in the Roman World', Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935390.013.85

Open Access

This article was published open access at OUP Academic. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935390.013.85